AI and work: a class issue

PART 1/3

by John Bratton

• Recently, Richard Hinton, the ‘Godfather of AI’, joined other members of the artificial intelligence (AI) intelligentsia in warning that AI may soon be more intelligent than humans. Since then, Keir Starmer has announced that AI will underpin Labour’s strategy to drive economic growth.

AI describes a field that combines computer science and datasets to mimic the problem-solving and decision-making capabilities of the human mind. AI can hugely benefit high-quality research and medicine, for example, but there are negatives.

These I will explore in the next issue of the Voice. Here, I aim to go beyond rhetoric proclaiming, ‘isn’t AI wonderful’ and explain that AI is neither ‘artificial’ or ‘intelligent’.

As a concept, intelligence enthrals humans — what it is, how it is measured and so on. Intelligence has been conceptualised in an abstract way, a property of internal thought processes and reasoning called rationality.

Alternatively, it has been theorised in a concrete way, as external observable intelligent behaviour — a combination of life-experience, reasoning, and judgement.

The idea that machines can ‘think’ — has its roots in European Enlightenment. Immanuel Kant’s (1724-1804) intellectual idea was that the human mind is not a blank slate, it’s an active agent in understanding the social milieu.

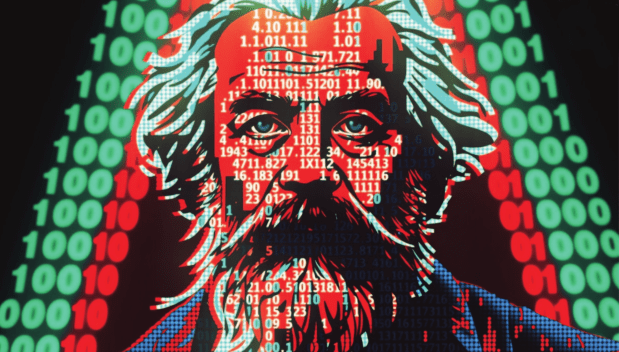

Karl Marx (1818-1883) challenged the idea that machines can think independently of humans. He proclaims the superiority of human intelligence in a famed observation:

“A bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he [sic] erects it in reality.”

Thus, every creative object must first exist in the imagination of the human mind. These intellectual ideas and prescient observations still resonate in AI debates.

The present-day debate on AI contains mythologies. First, that intelligence exists independently from the context of the wider social-economic, cultural conditions which inform and shape it. And second, that AI-based machines are equivalent to human minds.

The first myth was interrogated by Mike Cooley in Architect or Bee? (1980) Cooley, an engineer and union leader, argues that unlike computers, human imagination has no limits.

Moreover, human intelligence brings with it a cultural dimension: ‘Science and technology is not neutral… The choices are essentially political and ideological rather than technological’.

To illustrate, he argues that Computer-Aided-Design is deliberately designed to diminish human intelligence and enhance machine intelligence. About the second myth, that human intelligence can be codified by computers goes to the heart of how AI is understood.

Most mainstream definitions suggest AI imitates human-like behaviour, independently from human cognition. For some, AI is seen as an “intelligent agent” with a human quality and capacity to “learn” by recurrent iterations through a dataset.

In contrast, others define AI more broadly, asking the question, what socio-economic forces shape AI? This prism contends that AI is neither ‘artificial’ nor ‘intelligent’ but a product of human labour, culture, and values.

Uncharitable perhaps, but this view has drawn comment that ChatGPT, drawing upon massive datasets are little more than “stochastic parrots”.

Narrow definitions of AI neglect the fact that algorithms are created by humans, typically white, young men in the Global North.

For example, there is evidence that algorithms used for recruitment exaggerates racial phenotypes and creates overly sexualised female avatars.

I define AI as an attempt to build and program intelligence into an advanced machine and that performs actions effectively in a myriad of different situations.

The key word is “program” because it draws attention to the necessary human input that build non-biological intelligence through algorithms and datasets.

It recognizes that algorithmic structures are a socio-cultural construct, shaped by the social world within which they are produced, embedded in a culture of masculinity and gender inequalities and, crucially, encapsulating a particular set of worldviews in a computational routine, which reproduces social injustices.

The long-term goal of AI billionaires is not to create an encyclopaedia of the world but to be the encyclopaedia. Capital’s impulse to colonise knowledge dislodges the notion that AI is politically neutral, rather it reflects and reproduces unequal power structures in society.

Generative AI provides a prism to see and interpret the world in a particular way. A key takeaway is that AI is not politically neutral, but value laden.

That AI systems can be used by oligarchs to dominate markets, shape knowledge, and increase their power. In this context, AI is a class issue. In the next issue of the Voice, we will look at the effects of AI on work and society.

• John Bratton is co-editor (with Laura Steele) of ‘AI and Work: Transforming Work, Organizations & Society in an Age of Insecurity’ — published by Sage, January 2025

Subscribe now to receive the regular Voice newspaper PDF

https://scottishsocialistvoice.wordpress.com/subscriptions/

Leave a comment